How do you efficiently compute for a positive integer ? Take as an example. You could take and repeatedly multiply by 14 times. A better way to do it, however, is this:

A shorter way to write this is , where each quantity is obtained by multiplying two of the previous quantities together. We can write it even shorter as 1,2,3,5,10,15, where only the exponents are written. Here each number is obtained by adding together two of the previous numbers. This is called an addition chain and is at the heart of studying the optimal way of evaluating powers. There is no simple expression that computes the minimal number of multiplications needed to evaluate . A list, however, is available from The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, where the first 40 entries are

0, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4, 3, 4, 4, 5, 4, 5, 5, 5, 4, 5, 5, 6, 5, 6, 6, 6, 5, 6, 6, 6, 6, 7, 6, 7, 5, 6, 6, 7, 6, 7, 7, 7, 6, …

We see that , which shows that the addition chain 1,2,3,5,10,15 is indeed the shortest possible, and it follows that the procedure shown above to compute required the minimal number of multiplications.

Since the numbers in an addition chain grows the fastest by doubling the previous item, it is fairly easy to see that

(This, and other results related to the evaluation of powers and addition chains can be found in The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2, Section 4.6.3.)

An algorithm that comes close to this optimal bound is the binary method, which relies on these simple relations:

A recursive algorithm could readily be made from these, but we wish to have an iterative algorithm. The key here is to consider the slightly more general problem of evaluating . Here we have the relations:

This leads immediately to the following C++ code:

number_t power(number_t y, number_t x, unsigned n) {

while (n) {

if (n % 2 == 0) {

x *= x;

n /= 2;

} else {

y *= x;

n--;

}

}

return y;

}

A slightly improved version (and maybe a bit less elegant) is the following:

number_t power(number_t y, number_t x, unsigned n) {

if (!n) return y;

while (n > 1) {

if (n & 1) y *= x;

x *= x;

n >>= 1;

}

return y*x;

}

This algorithm performs multiplications of the type and multiplications of the type , where is the number of 1s in the binary representation of , so all in all it requires

multiplications (sequence A056792 at OEIS).

So now we can evaluate fairly efficiently. To evaluate we can simply use this routine by setting . But that wastes one multiplication because the first time we perform it will be redundant. Instead we could use power(x, x, n-1), but that could increase the number of multiplications for even . A good way to evaluate is this:

number_t power(number_t x, unsigned n) {

if (!n) return (T) 1;

while (!(n & 1)) {

x *= x;

n >>= 1;

}

return power(x, x, n-1);

}

This way, when executing power(x, x, n-1), n will always be uneven. This saves one multiplication compared to using just power(1, x, n), so it requires

multiplications (sequence A014701 at OEIS).

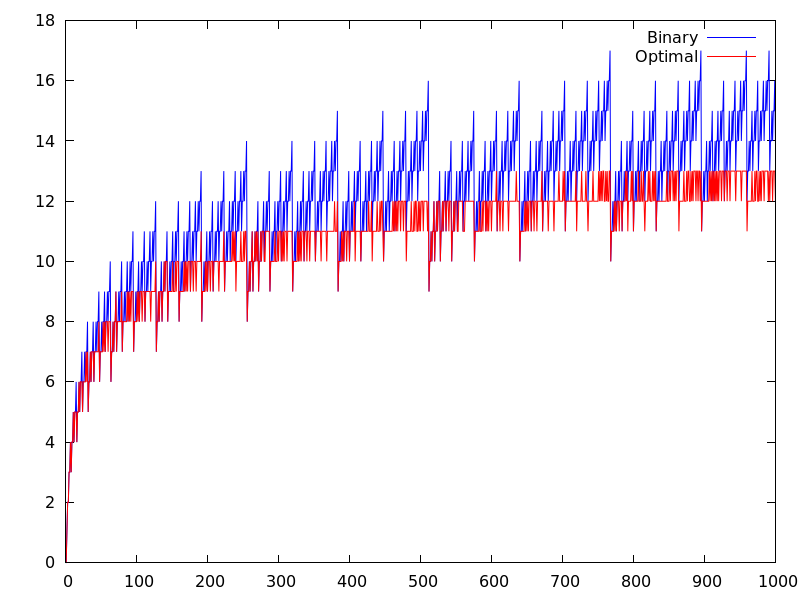

As mentioned above, this algorithm is not optimal, but it is not bad either. In fact, 15 is the smallest value of for which the binary algorithm does not use the minimal number of multiplications. Figure 1 below compares the number of multiplications needed by the binary algorithm to the minimal number possible.

Note also that we have only talked about minimizing the number of multiplications. What if a different cost is associated with each multiplication? For instance, the basic multiple-precision multiplication algorithm described in an earlier post has a cost propertional to if the factors have and digits, respectively. Using this cost model, the binary algorithm is actually optimal. This was shown by R. L. Graham, A. C.-C. Yao, and F.-F. Yao in Addition chains with multiplicative cost, Discrete Math., 23 (1978), 115-119 (article available online).